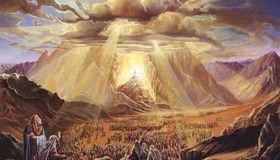

Israel’s Reaffirmation of Vows

If one reads the narrative of the giving of the Torah on Mount Sinai purely through the Biblical lens, unaided by Rabbinic commentary, the acceptance of the Torah on the part of Israel appears to be totally volitional. The shorter version of Israel’s formal acceptance reads: “The entire people responded together and said, ‘All that the Lord has spoken we shall do.’”1 The longer, more famous version reads: “They said, ‘All that the Lord has spoken we shall do and we shall hearken (to).’”2 In Hebrew, “Na’aseh ve-nishma‘.”

Comes the Talmud and injects an unforeseen element of coercion:

“They stood at the bottom of the mountain.”3 Said Rav Avdimi bar Hama bar Hasa: (This) teaches that the Holy One, blessed be He, suspended the mountain over them as a vat and said to them, “If you accept the Torah, good, and if not, there will be your burial (place).

Said Rav Aha bar Ya’akov: From here there is a great protest (i.e., grounds for annullment) of the Torah.

Said Rava: Nonetheless, later they accepted it in the days of Ahashverosh, for it is written, “The Jews fulfilled and accepted.”4 They fulfilled that which they already accepted.5

Rashi, the all-time great Talmudic commentator, adopts a relatively conservative posture. Commenting on the words “moda‘a raba” (“great protest”), Rashi writes: “Should He summon them for judgment (saying), ‘Why have you not fulfilled that which you have accepted upon yourselves,’ they have an answer, that they accepted it under coercion.”

Evidently Rashi found it inconceivable that at any time in Jewish history there actually took place an annulment of the Torah on the grounds that it had been accepted at Sinai under duress. At most, this was a theoretical argument that was never utilized.

Nahmanides’ comment on this passage in the Talmud is by comparison so bold as to make one shudder. He writes:

It seems to me that though from the onset they had grounds for annulment, nonetheless He gave the Land to them only in order that they fulfill the Torah, as is explicit in the Torah in several passages, and it is written, “He gave them lands of nations and the toil of peoples they inherited, in order that they keep His statutes and guard His laws.”6 And they themselves did not object in the least and put up no protest but willingly proclaimed, “All that the Lord has spoken we shall do and we shall hearken (to).” Therefore, when they transgressed the Torah, He exiled them from the land. Once they were exiled they did protest the thing, for it is written, “That which arises in your spirit shall not come to pass, that which you say, We shall be as the nations, as the families of the lands, to serve wood and stone.”7 And as we say in the Agadah: “Ezekiel our teacher, a slave sold by his master, does he (i.e. the master) have any (claim) on him?” Therefore, when they entered the land a second time in the days of Ezra, they took upon themselves to accept it willingly, so that there could be no further complaints.8 And this coincided with the days of Ahashverosh, whereupon (God) took them out from death to life.9 And this was more beloved to them than the redemption from Egypt.10

For Nahmanides, unlike Rashi, the argument that the Torah had originally been accepted under duress did not remain in theory, but was actually presented in the gap between the destruction of the First Temple and the subsequent exile from the land, and the return to the land in the days of Ezra. For those seventy years of Babylonian captivity there was, if we understand Nahmanides correctly, an actual abrogation of the treaty between God and the Jewish nation whereby the nation was dutybound to keep the commandments of the Torah.

What is all the more remarkable in this paragraph of Talmudic exegesis is the man who authored it. None other than Moses Nahmanides (1194-1270), who was locked in mortal combat with the Catholic Church, all-powerful in Spain! Christianity is famous (or infamous) for its supercessionist theology, whereby the historic people of Israel is supplanted by “Verus Israel,” the “True Israel,” and the Old Covenant is replaced with the New Covenant. In Barcelona in the year 1263, Nahmanides would engage in a religious disputation with an apostate Jew by the name of Pablo Christiani. In that disputation, Nahmanides would valiantly parry against the claims of the dominant religion. Objectively speaking, I am not prepared to offer the exact or even approximate date in which Nahmanides composed his commentary to Tractate Shabbat. Be that as it may, it is simply not possible that at any time in his literary career Nahmanides was oblivious to the claim made by Pauline Christianity that the covenant made with Israel at Sinai had been abrogated with the arrival of Jesus.11

And yet it is just Nahmanides, living as he did in a Catholic monarchy bent on the conversion of its Jewish inhabitants, who dared to interpret our passage of the Talmud in such a bold and daring manner. This should give us pause for thought.

Is it possible that Nahmanides understood the passage in the Talmud to have been conceived in a polemic vein, as a sort of refutation of the claims of Pauline Christianity? Did Nahmanides believe that Rava’s retort was designed to serve as a “teshuvat ha-minim” or “teshuvat ha-notsrim”?12 Assuming that we are on the right track, the counterargument to Christianity would work in the same way that in 1796 Edward Jenner saved the English population from smallpox with “vaccine” (from cowpox), or that a century later in 1895 Albert Calmette developed an antivenom for the treatment of snakebite by injecting a small amount of snake venom into an animal (horse or sheep) and harvesting the antibodies from the animal’s blood. In Aramaic, this strategy is referred to as “Leshaduye beh narga mineh u-veh.” By introjecting the concept of abrogation of the covenant and revealing that the very breaking of the vows had indeed been followed by a renewal of the vows (to borrow from the nuptial terminology deemed by the Rabbis appropriate for the covenant at Sinai), Paul would have been discomfited.

* Copyright 2013 Bezalel Naor

——–

- Exodus 19:8. Cf. Exodus 24:3 “The entire people responded (in) a single voice and said, ‘All the things that the Lord has spoken we shall do.’”↩

- Exodus 24:7.↩

- Exodus 19:17.↩

- Esther 9:27.↩

- TB, Shabbat 88a.↩

- Psalms 105:44, 45.↩

- Ezekiel 20:32.↩

- See Nehemiah chap. 10 regarding the “treaty” (“amanah”)—or to use my nuptial terminology, “reaffirmation of vows”—that was struck in the days of Ezra and Nehemiah. Inter alia, based on the passage in Nehemiah, Rabbi Joseph Dov Baer Halevi Soloveitchik of Brisk posited that nowadays Shemitah (observance of the Sabbatical Year) must be considered “divrei kabbalah,” a halakhic status which carries more weight than a rabbinic ordinance (“de-rabbanan”). This novel thesis was refuted by Rabbi Abraham Isaac Hakohen Kook in his work devoted to the laws of Shemitah. See Rabbi Soloveitchik,She’elot u-Teshuvot Beit Halevi, Pt. III, no. 1, par. 6 (2); Rabbi Kook, Shabbat ha-Arets, Introduction, chap. 8.↩

- TB, Megillah 14a.↩

- Hiddushei Ramban, Shabbat 88a.↩

- Some years ago Rabbi Moshe Rosenwasser examined several passages in Nahmanides’ commentary to the Pentateuch against the backdrop of Christian theology. See Moshe Yehudah Rosenwasser, “Peirush ha-ramban ‘al ha-torah le-‘or ha-‘imut ‘im ha-notsrut,” HaMa‘ayan 47:2 (Tevet 5767).↩

- One is tempted to link this statement of Rava (“Nonetheless, later they accepted it in the days of Ahashverosh, for it is written, ‘The Jews fulfilled and accepted.’ They fulfilled that which they already accepted”) with the subsequent dialogue between Rava and an anonymous sectarian who held Israel up to ridicule “for having put their mouths before their ears” at Sinai. The sectarian’s point was that Israel were hasty in committing to accepting the Torah before deliberating whether they would in fact be capable of keeping to their commitment. (See Shabbat 88.) Though the identity of the sectarian is not disclosed, this attempt to impugn or somehow vitiate the Sinaitic covenant may reflect a Christian supercessionist agenda.As convenient as it is to link the two statements of Rava, a monkey wrench is thrown our way by the reading of the BaH in the first instance: “Rabbah” rather than “Rava.”An obvious question arises: Why would Rava, living in Babylonia, dialogue with a Christian concerning the covenant at Sinai? This question was already posed by Richard Kalmin. He points out that the interaction between Rava and a heretic (min) in Shabbat 88a-b is one of only two cases recorded in the Babylonian Talmud where there is interaction between a Babylonian rabbi and a heretic. Kalmin offers two possible solutions: 1) Later Babylonian Amoraim such as Rava are frequently depicted as behaving in accordance with Palestinian models. 2) The name “Rava” is frequently confused with the name “R. Abba.” There were apparently several Amoraim named R. Abba, and all of their statements, as far as we can determine, derive from Palestine. It is possible, therefore, that even this narrative depicts a dialogue between a heretic and a rabbi in Palestine. Kalmin points out in this regard that this very jab at a “rash nation who put their mouths before their ears” was directed by a sectarian at Rabbi Zeira immediately upon arrival in Erets Israel (see Ketubot 112a). See Richard Kalmin, Jewish Babylonia between Persia and Roman Palestine (Oxford University Press, 2006), pp. 100; 223, note 59.

Originally published in Torah Musings: http://www.torahmusings.com/2013/08/nahmanides-theological-boldness/