At this time of year, we read of the antagonism toward Joseph on the part of his brothers, primarily Judah. Obviously, Joseph’s brothers felt threatened by him in some way. Our holy teacher Rav Kook explains this opposition of Joseph and Judah. Rav Kook takes what might appear to be merely personal enmity up to […]

Vayyigash: The Psychology of the “Yitsra de-Sin’at Hinam” Part 1

Bezalel Naor

Parashat Vayyigash

The Psychology of the “Yitsra de-Sin’at Hinam”

Part 1

We read in this week’s Torah portion of the rapprochement between feuding brothers, specifically Joseph and Judah. This theme is reflected in the Haftarah, the reading from the Prophets, which is designed to act as a mirror image of the Pentateuchal reading.[1]

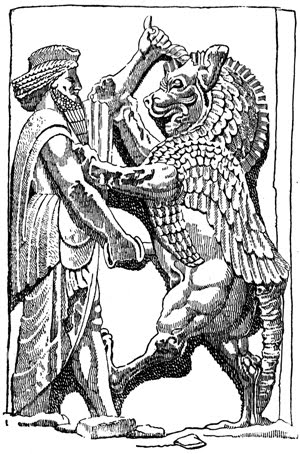

By the time of the Prophet Ezekiel, the nation of Israel had been divided into two kingdoms: the Kingdom of Israel (or Joseph) in the North, and the Kingdom of Judah in the South. Ezekiel is commanded by God to perform a symbolic act (referred to in Nahmanidean terminology as a “po’al dimyoni”). He is to take two sticks. Upon one he is to write: “For Judah.” Upon the other he must write: “For Joseph.” He is then to bind the two sticks together as one. This is to symbolize that the Lord will reunite Joseph and Judah.

When the children of your people will say to you, Will you not tell us what these are to you? Speak to them,

Thus said the Lord, Behold I am taking the Tree of Joseph…and the tribes of Israel, his companions, and

placing them together with the Tree of Judah, and I shall make them into one tree, and they shall be one in

my hand.[2]

The brothers’ sin of selling Joseph into slavery was so grievous that one of the great teachers of Torah who perished in the Holocaust, Rabbi Elhanan Wasserman (Rosh Yeshivah of Baranovich), opined that the blood libels brought against the Jews throughout the centuries were divine retribution for the nation’s collective guilt in having sold the righteous Joseph!

Unfortunately, the Satan of sin’at hinam (literally, “free hatred”), senseless hatred and infighting between members of our own people, still dances among us. How does one eradicate this bane?

The Talmud tells us that the First Temple was destroyed on account of the three cardinal sins rampant during the First Temple era: idolatry, sexual immorality and murder. The Second Temple on the other hand, was destroyed due to the sin of sin’at hinam, internal hatred of Jew for Jew.[3]

Rav Kook is famous for having said that the corrective to sin’at hinam (“free hatred”) is ahavat hinam (“free love”). Just as the Temple was destroyed on account of senseless hatred, so it will be rebuilt by the power of senseless love that one Jew has for another.

Rabbi Kook had a dear friend, a fellow Lithuanian kabbalist by the name of Rabbi Pinhas Hakohen Lintop (Rabbi of Birzh or Birzai, Lithuania). Rabbi Lintop had a different idea how we might solve the ongoing problem of sin’at hinam.

According to the Talmud, at the very onset of the Second Temple, a Great Assembly was convened to abolish the yitsra de-‘avodah zarah, the drive for idolatry. The Men of the Great Assembly knew that it would be pointless to erect a Second Temple as long as the compulsion for idolatry was yet intact. As long as Jews were yet drawn to idolatry, it was a foregone conclusion that this new temple would suffer the same fate as its predecessor. So the Anshei Knesset ha-Gedolah (the Men of the Great Assembly) came together and through their power of prayer, abolished the entire phenomenon of idolatry.[4]

Rabbi Lintop reasoned that what is required in our own day—so that we may rebuild the Temple—is to once again convene a Knesset ha-Gedolah, a Great Assembly, this time to abolish the yitsra de-sin’at hinam, the driving compulsion for senseless, irrational hatred so rampant among us.

In fact, Rabbi Lintop hoped that the Knessiyah ha-Gedolah of the World Agudath Israel movement, convened in Vienna in the month of Ellul, 5683 (1923), would be the golden opportunity for doing away with infighting, once and for all. To this end, he wrote an address to that great congress, in which he outlined his plan. He requested of Rabbi Hayyim Ozer Grodzenski of Vilna, the acknowledged leader of the generation, that he read the address from the podium!

Needless to say, Rabbi Lintop was sorely disappointed when the Knessiyah ha-Gedolah, despite its truly remarkable achievement in unifying disparate elements of the Jewish People—hasidim and mitnagdim, Hirschians from Frankfurt and Mussarites from Slabodka, et cetera—failed to live up to the potential that the visionary expected of it

Perhaps the saddest commentary on the failure of the Knessiyah Gedolah was the fact that at the convention itself, abuse was heaped upon Rav Kook of Jerusalem, Rabbi Lintop’s dearest friend and soul “brother.” For that reason, the saintly Rabbi Israel Meir Hakohen (author Hafets Hayyim), felt forced to walk out of the convention in demonstrative protest, locking himself away in his hotel room, awaiting his return to Radin.

We need to discuss the psychology (and perhaps also the neurology) of the “yitsra de-‘avodah zarah” and the “yitsra de-sin’at hinam” (to adopt Rabbi Lintop’s felicitous term) …

(To be continued)

Parashat Vayehi

Bezalel Naor

Father Jacob: A Godly Being?

There is something extremely puzzling in this week’s Torah portion. Father Jacob commands his son Joseph not to bury him in Egypt but rather together with his fathers (in the Cave of Machpelah). Commenting on the words “Do not bury me in Egypt” (Genesis 47:29), Rashi writes: “So that the Egyptians don’t make me into an idolatry” (Genesis Rabbah). One wonders why the Egyptians would be so inclined to idolatrize Jacob. After all, Jacob (unlike his son Joseph) was not a ruler of Egypt. Usually, only kings of Egypt would be deified after their death.

Parashat Shemot

“L’Exil de la Parole”

“Exile of the Word”

Bezalel Naor

Parashat Shemot

Shovavim Tat

We begin this week a special period in the Kabbalistic calendar known as “Shovavim Tat.” This is an acronym for the Torah portions that we will be reading during this time span: Shemot, Va’era, Bo, Beshalah, Yitro, Mishpatim, Terumah, Tetsaveh.

The meaning of the Hebrew word “shovavim” is “naughty,” as in “Return naughty children” (“Shuvu banim shovavim”) (Jeremiah 3:14). According to the Kabbalists of old, this is an especially propitious time to return human seed scattered by nocturnal emission.

But this “tikkun” or fixing of souls may be taken to more abstract levels. In the heyday of the East-European Hasidic movement founded by Rabbi Israel Ba’al Shem Tov, the great Hasidic “maggidim” or preachers would wander from town to town during this period to gather in the human elements that had been dispersed, bringing lost souls back to their divine source.

Perhaps in our own day the work of the “tsaddik” devoted to the cause of gathering in the dispersed souls may be made easier by the Internet. No longer must the righteous trudge through the deep snow to reach his destination. His work may now be carried out in Cyberspace.

Exile of the Word

According to the Zohar, speech was in exile in Egypt. The French Jewish thinker Andre Neher adopted this theme from the Zohar as the title of one of his studies, L’Exil de la parole, translated into English as Exile of the Word.

Developing this idea, Rabbi Isaac Luria punned that the deliverance from Egypt, Pesah (Passover) is actually two words: Peh sah (“talking mouth”). The redemption consists in the liberation of the word.

Whereas the Torah itself discusses only the speech impediment of Moses, who by his own admission was a stutterer and stammerer (kevad peh u-khevad lashon),[1] our great thinkers portray the existential condition of the Children of Israel in Egypt as one of collective muteness. Rabbi Joseph Baer Soloveitchik of Boston once remarked that the expressions the Torah employs to describe the Children of Israel’s reaction to the oppression of slavery (ze’akah, shav’ah, na’akah)[2] evoke the anguished outcry, the moaning and groaning of a wounded animal; nothing even approaching the eloquence of prayer. One might go so far as to say that their response is “preverbal.” (Rabbi Soloveitchik was preceded in this observation by Rabbi Abraham Tsevi Margaliyot, eminent disciple of the Hasidic Rabbi Tsadok Hakohen of Lublin.)[3]

One muses aloud that this is perhaps the symbolism of the Lithuanian custom of eating eggs at the Seder table on the night of the 15th of Nissan. Eggs have no “mouth.” They symbolize muteness. For this reason, traditionally they are eaten by mourners. As a result of the loss of a loved one, the mourner is plunged into a state of muteness. The eggs would come to remind us of the exile of the word in Egypt.

The one Hebrew who stands out as an exception to the mute scenario of Egypt is: Shelomit bat Divri. Rashi interprets her name in the following manner:

Shelomit—For she would chatter, “Shalom to you! Shalom to you!” She would chatter on, extending greeting to all. Bat Divri—She was (overly) talkative, speaking with everyone…

(Rashi, Numbers 24:11)

Rashi goes on to explain that Shelomit’s behavior led to her undoing, whereby she bore a son to an Egyptian. (This Egyptian man was none other than the Egyptian overseer slain by Moses in our Parashat Shemot.)[4] But short of committing adultery, her talkativeness alone was inappropriate behavior in that state of “exile of the word.” Just as it is improper in a house of mourning (beit ha-‘evel) to extend the greeting of “Shalom,” so in Egypt the greeting of “Shalom” was certainly out of character.

[1] Exodus 4:10. Interesting is Onkelos’ Aramaic version of “kevad lashon”: “’amik lishan” (literally, “deep of tongue”). Might this be an allusion to the Rabbinic tradition that Moses had a very deep voice? See Rashi to Exodus 2:6, s.v. ve-hineh na’ar bokheh: “His voice like that of a lad.” While yet an infant, Moses possessed the voice of a pubescent boy.

[2] Exodus 2:23-24.

[3] See Rabbi Abraham Tsevi Margaliyot, Keren ‘Orah, Va’era.

[4] See Rashi Exodus 2:11 and Leviticus 24:10.

Parashat Va’Era: Messages from G-d

Parashat Va’Era

Messages From G-d

Bezalel Naor

Parashat Va’Era

Freedom Movements

How do we know that we may make use of the “bat kol” (heavenly voice)? For it says, “Your ears will hear a word from behind you” [Isaiah 30:21] (Talmud Bavli, end Tractate Megillah).The explanation of this is that when the Children of Israel are free men, then the Word proceeds to Israel in a direct fashion, and from them it spreads to the entire world. However in exile, they [i.e., the Children of Israel] hear it only from behind them. When God wishes to send a new influx to Israel, the nations sense this beforehand, and they bond together…and create a tumult…and Israel understand through them which light, which new influx of energy God is busy opening now. So it is now. He who desires to understand the tumult…understands from this that God is busy opening for them a new light that they may be free men. And since Israel do not have an explicit ilumination, just that they figure out on their own based on the opposite’s behavior, it is dubbed a “bat kol” (heavenly voice). And this is what the verse means by “Your ears will hear a word from behind you.” Namely, from the nations, who are referred to as “ahorayim” (the rear). For the desire and quest of the Children of Israel to be free men is the opposite of the nations…(Rabbi Jacob of Izhbitsa and Radzyn, Beit Ya’akov, end Va’Era)

Parashat Bo: The Enigmatic Existence of Evil

Parashat Bo

The Enigmatic Existence of Evil

Bo el Par’oh / Come to Pharaoh

Bezalel NaorThe Torah portion begins with the words “Vayyomer YHWH el Moshe, Bo el Par’oh” (“The Lord said to Moses, ‘Come to Pharaoh’”).[1] Moses is commanded by God to appear before Pharaoh and demand that Pharaoh send free the People of Israel. The obvious question arises. Would it not be more correct syntactically to command “Lekh el Par’oh” (“Go to Pharaoh”), rather than “Bo el Par’oh” (“Come to Pharaoh”)?

The Rebbe of Kotsk, Rabbi Menahem Mendel Morgenstern (1787-1859), one of our boldest and most daring thinkers, replied that one must not forget who is speaking: God. So the statement is formulated from God’s perspective. From God’s perspective, it is perfectly correct to say “Come to Pharaoh” because God is found right there in the very midst of Pharaoh!

This is an extremely powerful, even brutal realization that goes to the very heart of the problem of evil. All philosophic systems must ultimately come to terms with the problem of evil. If God is good, then how does evil arise in this universe? The Persian religion of Zoroastrianism was conveniently able to posit two opposite forces at work in the world: Ahura Mazda (or Hormazd, Hormoz),[2] the god of good and light, versus Ahriman, the god of evil and darkness. However, the ancient Israelite prophet Isaiah railed against this dualistic perception of reality, upholding a strict monotheism, a single deity who “yotser ‘or u-bore hoshekh, ‘oseh shalom u-bore ra’, ani YHWH ‘oseh kol eleh” (“forms light and creates darkness, makes peace and creates evil; I am the Lord Who does all this”).[3]

With this sharp, epigrammatic koan of the Kotsker Rebbe, there is driven home to us in the most forceful manner that Pharaoh, the very symbol of evil, has no existence independent of God. Ultimately, the evil in the world is authored by God. Judaism could not afford the dualism of the Persian prophet Zoroaster (or Zarathustra). In the simple, yet eloquent words of the Prophet Isaiah: “bore ra’” (“[The Lord] creates evil”).

In our daily morning prayer established by the Sages who postdated Isaiah, Isaiah’s stark, shocking statement has been emended to read: “Barukh ata YHWH, Eloheinu, melekh ha-‘olam, yotser ‘or u-bore hoshekh, ‘oseh shalom u-bore et ha-kol” (“Blessed are you, Lord, our God, King of the Universe, who forms light and creates darkness, makes peace and creates the all”).

Rav Kook explains the difference between the Prophet Isaiah’s formula and that instituted by the Sages in our prayer. Isaiah was describing the “facts on the ground,” so to speak. One cannot deny the facticity of evil in our world. Unfortunately, the world abounds in evil.

The Prophet described the reality of our plane of existence. The Sages understood that on a higher level of reality (referred to as “the All”), the seemingly discrete, disparate, disjoint elements bond together in a simple unicity:

The prophecy, which is intended to inculcate a moral lesson in opposition to philosophies that would undermine monotheism, is stated in terms of human perception: “creates darkness,” “creates evil”… But we in our prayer, inasmuch as it our objective to tell the truth of the honor of the Lord, are correct in saying “creates the all.”… But in order “to mention the attribute of day by night, and the attribute of night by day,”[4] i.e., the principle of the singularity of divine rule throughout all the opposite manners in which existence is governed—both general and specific—we mention too that which is our common perception: “creates darkness.”

However, since the purpose of the blessing is also to bless the Lord for His lovingkindness—“‘olam hesed yibaneh” (“the world is established with lovingkindness”)[5]—it is worthy to conclude the blessing with the acknowledgment of the truth, that the Lord created no evil, and there is in existence no absolute evil, and the perceived evil is joined to the totality to perfect the good, so that evil is subsumed under the term “the All.”[6]

According to Rav Kook, the relation of the text of the prayer to that of the prophecy is exactly the reverse of what we have generally been led to believe. Most of us assume that Isaiah spoke truth itself and that the Rabbis in formulating the prayer “toned down,” ameliorated or even censored that truth, substituting a euphemism “all” for Isaiah’s unflinching “evil.” Comes Rav Kook and tells us the exact opposite. The ultimate truth is that formulated by the Sages, the Men of the Great Assembly: In reality there is no evil. Once evil has been grasped as part of the totality of existence, it disappears from our vision. It was the Prophet Isaiah, who for the purposes of moral exhortation in combatting philosophies that would deny pure monotheism, overstated the case for evil, couching reality in terms convenient to the common perception of man.

Although Rav Kook chalks the difference of the prophecy and the prayer to their varying objectives—moral exhortation versus singing the praises of God, Who is ultimately a loving God—one is tempted to explain the difference in terms of the prophet’s and sage’s differing perceptions of reality. When confronted with the problem of evil, the purview of the Prophet is circumscribed; the Sages’ grasp of reality is more comprehensive. At this point, one might invoke the famous maxim: “Hakham ’adif mi-navi.” (“The sage is superior to the prophet.”)[7] Based on their theodicy, the Men of the Great Assembly actually surpassed the Prophets.[8]

[1] Exodus 10:1.

[2] See TB, Gittin 11a and Tosafot ad locum, s.v. Hormin; TB, Sanhedrin 39a and Tosafot ad loc., s.v. Hormiz.

[3] Isaiah 45:7. The passage occurs within the context of a prophecy to Cyrus, King of Persia.

[4] TB, Berakhot 11b.

[5] Psalms 89:3. See also Genesis Rabbah 8:5: “Lovingkindness says, ‘He [i.e., Adam] should be created.’” It should be noted however that the words “asher amar ‘olam yibaneh” (“which said the world should be created”) are lacking in the original of ‘Eyn Ayah, and would therefore appear to be a gloss of Rabbi Tsevi Yehudah Hakohen Kook to his father’s work. (See next note.) The present writer hopes one day to deal with this and other issues concerning the composition of Rav Kook’s commentary to the Prayer Book.

[6] Rabbi Abraham Isaac Hakohen Kook, Siddur ‘Olat Re’iyah, Vol. I, p. 239; idem, ‘Eyn Ayah (Filber ed.), Berakhot, Chap. I, par. 160. The text of ‘Olat Re’iyah differs from that of ‘Eyn Ayah (Rav Kook’s commentary to ‘Eyn Ya’akov). Rav Kook’s son, Rabbi Tsevi Yehudah Hakohen Kook (1892-1981) adapted the section from ‘Eyn Ayah to the Siddur.

[7] TB, Bava Batra 12b.

[8] See Yer. Berakhot 7:3; TB, Yoma 69b; Rabbi Isaac Hutner, Pahad Yitshak—Hannukah, Ma’amar 8.

Rabbi Isaac Hutner was a disciple of Rav Kook during Rabbi Hutner’s early years in Jerusalem. (However, Rabbi Ahron Soloveichik once communicated to this writer in private conversation that he felt it an inexactitude to use the term “talmid” [disciple] to describe Rabbi Hutner’s relation to Rav Kook. Rabbi Hutner was the private teacher of Rabbi Ahron Soloveichik during the latter’s youth in Warsaw.)

Parashat Vayakhel-Pekudei

Bezalel Naor

The Tabernacle: A Virtual Erets Israel

Vayakhel-Pekudei

A major portion of the book of Exodus is taken up by a painstakingly detailed description of the construction of the Tabernacle (Mishkan) in the desert. The magnificent architecture has come to be associated with the name of Bezalel, the chief craftsman or artisan, the mastermind in charge of the design, lo, the “brains” of the operation. (The famous Bezalel Art School in Jerusalem, founded by Boris Schatz, was appropriately enough named after this extremely talented Biblical figure.)

Yet the question remains: Why should the Torah lavish so much attention upon the layout of this prototypical temple? Moses is not Frank Lloyd Wright. Whatever the Torah of Moses is (and that is open to some debate), it is not a manual of architecture.

I believe that a solution to this vexatious problem may lie in the famous words of Nahmanides’ Introduction to the Book of Exodus:

The text completed the Book of Genesis, which is the book of the creation of the world and the creation of all the creatures, and the events of the Patriarchs, which are sort of the creation for their seed, for all their events are illustrations, alluding to all that will befall them in the future. And after having completed the creation, the text commenced another book concerning the deeds that proceed from those allusions. The Book of Exodus is focused upon the first exile that was explicitly decreed, and upon the redemption from it. Therefore it begins with the names of those who descended to Egypt, and their number, though that had been written earlier [in the Book of Genesis], for their descent there is the beginning of the exile, from whence it commenced. Now the exile is not terminated until the day of their return to their place and to the level of their forefathers. When they went out of Egypt, though they emerged from the house of bondage, they would yet be considered exiles, for they were in a foreign land, straying in the desert. When they arrived at Mount Sinai, and made the Tabernacle, whereby the Holy One, blessed be He, restored his divine presence to their midst, then they returned to the level of their forefathers, upon whose tents rested the divine mystery, they [i.e., the forefathers] being the Chariot [of God]. And then they were considered redeemed (ve-‘az neheshavu ge’ulim) . Therefore this book concludes with the completion of the Tabernacle and the glory of the Lord filling it perpetually.[1]

The sentence that I have seen fit to italicize is a bold statement indeed. It would be a bold statement coming from any Jew, but all the more so from the pen of Nahmanides! Many years ago, the late Rosh Yeshiva of Ponevezh in B’nei Berak, the great Torah sage Rabbi El’azar Menahem Man Shach aroused the ire of many when he somewhat minimized the importance of the State of Israel by stating the rather obvious fact that the Jewish People experienced nationhood before ever arriving in the Land. He did not invoke Ramban or Nahmanides cited above. Nahmanides’ statement is perhaps even more daring than that of the Ponevezh Rosh Yeshivah: “And then they were considered redeemed!” Not having stepped foot on the holy soil of the Land of Israel, the People were already reckoned redeemed by virtue of the fact that they had regained their former spiritual height, inasmuch as the divine presence permeated the Tabernacle.

This statement, which seems to call into question the absolute necessity of dwelling in the Land, is all the more surprising having been uttered by none other than Nahmanides. Anyone at all familiar with Nahmanides, knows that among all the Rishonim or medieval giants, he stands out in his declaration of the centrality of the Land of Israel to Judaism. It is Nahmanides who writes at great length in his commentary to the Pentateuch that essentially the performance of the commandments (all the commandments, not just mitsvot ha-teluyot ba-arets, such as the various agricultural laws) pivots on the Land of Israel. He cites the Sifre (‘Ekev) to the effect that in performing commandments outside the Land, we are merely going through the motions, so that these observances not be forgotten.[2] It is also Nahmanides who (in his glosses to Maimonides’ Book of the Commandments) counts dwelling in the Land of Israel as a positive commandment, trailing off on the note that “dwelling in the Land of Israel is equal to all the commandments.”[3] Yet it is this same Nahmanides who issues our curious statement: “And then they were considered redeemed (ve-‘az nehshavu ge’ulim).”

I believe that it is because Nahmanides views the Land of Israel to be central to Judaism, that he is forced to conclude that the Tabernacle is, in so many words, a virtual Erets Israel. (In Hebrew, this logic is formulated as “ve-hi ha-notenet.”) Nahmanides would have been struck by a glaring omission from the Five Books of Moses: the Land of Israel. When the Five Books conclude, the People are yet outside the Land. Conceptually this is unthinkable. The solution? The Tabernacle in the desert constitutes a virtual Land of Israel. And this may be the solution to our original conundrum.

The Talmud states: “Had Israel not sinned, they would have been given only the Five Books of Moses and the Book of Joshua, because it [i.e., the latter] is the value of the Land of Israel (‘erkah shel erets yisrael).”[4] All the remaining books of the Bible, the Prophets and Writings (Nevi’im u-Ketuvim) are non-essential. The Five Books of Moses and the Book of Joshua are of the essence. But within the very Five Books of Moses there resides a virtual Book of Joshua that, short of actual entry into the Land of Israel, assumes the value of the Land of Israel (‘erkah shel erets yisrael), namely the portion of the Book of Exodus devoted to the work of the Tabernacle. And just as the Book of Joshua will detail ever so lovingly the geography of the Land of Israel, so our section of the Torah will sumptuously, lavishly detail the contours of this Land before the Land: the Mishkan or Tabernacle in the Wilderness.

Reader of the Week: Shimshon Alpert

Have you read an article or dvar Torah on orot.com or watched a shiur that really got you thinking? Send us your reflections to info@box5597.temp.domains and you may be the featured reader of the week!

Reader of the Week: Shimshon Alpert on “Yitsra de-Sin’at Hinam”

To read the article “Yitsra de-Sin’at Hinam,” click here

The only way to stop baseless hatred is to adopt the derech of R. Kook – baseless love. Maybe the haters will move toward the middle, which is a big step forward. But one must avoid the huge stumbling block: the conditionality that’s embedded within Judaism itself which encourages judgmentalism, criticism, self-righteousness, harshness, severity — all things that are connected to hatred and which are opposed to the most fundamental principal of the Torah, “love your neighbor as yourself.”

In essence, do not avoid Judaism, but rather the conditionality that’s embedded in Judaism.

Shimshon Alpert

Reader of the Week: Greg Yashgur

Have you read an article or dvar Torah on orot.com or watched a shiur that really got you thinking? Send us your reflections to info@box5597.temp.domains and you may be the featured reader of the week!

Reader of the Week: Greg Yashgur on “Yitsra de-Sin’at Hinam”

To read the article “Yitsra de-Sin’at Hinam,” click here

It is not hate, it is an observation. Zealousness in thinking that someone knows what G-d wants is the root cause of sinat chinam, the rest has reasons, so much for 24,000 R. Akiva’s students for who we still fast and for 6,000,000 Shoa victims for whom we do not.

My thinking is that if ‘derech eretz kodem Torah,’ basic midot (manners) and ethics must precede Torah learning; if that condition is not met, the edifice on flimsy foundation does not stand and will not stand.

The book of Genesis of Avot (fore-fathers) precedes the books of Commandments and for a reason. First ideals then commandments. Commandments without ideals are worthless.

No one can ban baseless hatred by decree. That is the whole point to understand that there is an evolution in civic conscience over period of human history and if we, Jews, have anything to say to the world, today, and if we want the world to hear, then we should embrace the world that also was created in G-d’s image and that this embrace is the foundation for a dialog. With no respect there is no equality and no dialog. We start from ourselves.

On the other hand if we are too premature with the message then it is false-Messianism. We accumulated too many klipot, impurities, that unless we seek the truth with our strengths, the situation will not improve.

Thank G-d that life is stronger than theory. The beginning of 20th century showed orthodoxy being decimated by influence of human endeavors and new thinking (of Rav Kook in particular) was planted. Same thing will happen again and something good again will be attained. Everything is evolving and will go through its dialectical iterations.

Let’s keep faith.

Greg Yashur