Review Essay

by Rabbi Yosef Gavriel Bechhofer

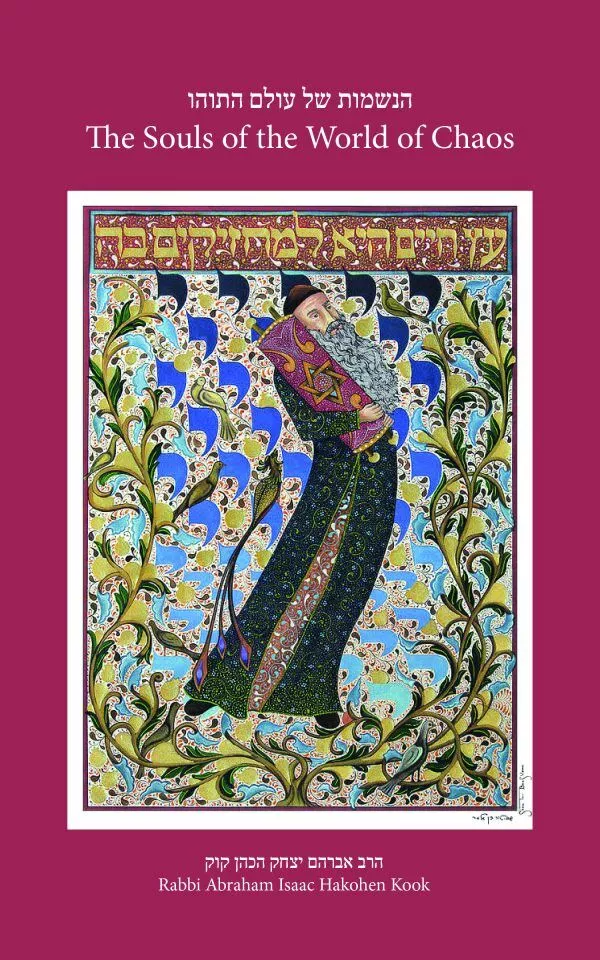

The Souls of the World of Chaos

by Rabbi Abraham Isaac Hakohen Kook

Translation, Introduction and Notes by Bezalel Naor

Orot/Kodesh 5783/2023

Today is an appropriate day to write this review. It is 3 Elul, Rav Kook’s 88th Yahrzeit. It is also shortly after the end of Shiv‘ah for the author of the Mikhtav Berakhah (Letter of Blessing) that appears at the front of the book, Rav Moshe Zuriel, of blessed memory. As Rav Zuriel’s letter is very significant, and is not translated in this volume, it is worthwhile quoting some excerpts here.

Rav Zuriel writes that there is no generation in which there are no public problems, stresses and pressures. This is how God designed the world, that there be constant clashes of opinion, forcing one to confront these challenges, find courage within oneself, and fortify oneself with all one’s capacities to bring a measure of blessing to this world. Barriers were created for mankind to surmount.

Rav Kook, writes Rav Zuriel, was the greatest champion of emunah (faith). He had the clarity of Nachum Ish Gamzo, to pronounce: “Gam zo le-tovah” (“This too is for the good”). Rav Kook was therefore able to see the internal rebellions, the chutzpah to deny God’s existence, the constant attacks upon the fulfillment of mitsvot, with the eyes of those familiar with the inner secrets of the Torah; those who know that even the apparent disruptions of the divine plan are also part of the plan.

Rav Zuriel acknowledges that the Souls of the World of Chaos is one of the toughest nuts to crack in the broad spectrum of Rav Kook’s writings. “To say that the souls of these heretics are higher than the souls of the simple keepers of the faith, who can explicate this?”

Thus, we are given to understand from the outset how difficult a task Rabbi Bezalel Naor undertook in this work. Yet, already in his introduction, he eloquently weaves the threads of the doctrines of the Vilna Gaon, of Chabad and of Radzyn, into a striking pattern of iconoclasm as a manifestation of sanctity.

There follows—in two pages!—the original Hebrew text of The Souls of the World of Chaos. It is these two pages that have generated a book of 220 pages.

Rabbi Naor’s masterful translation exposes the English reader to Rav Kook’s seemingly antinomian words:

The great idealists want a beautiful and good order, so firm and mighty, that it has no comparison or foundation in the world—therefore they destroy that which is built in conformity to the world …

Souls of chaos (neshamot de-tohu) are higher than the souls of establishment (neshamot de-tikkun) … They seek a very great light; they cannot tolerate whatever is finite, defined and estimable …

They [i.e., the souls of chaos] are revealed in the brazenfaced of the generation (‘azei panim she-ba-dor). The principled wicked (ha-resha‘im ba‘alei ha-prinzipim), the sinners who flaunt their sins (le-hakh‘is ve-lo le-tei’avon), their soul is very high—from the lights of chaos (’orot de-tohu) … But the essence of courage contained in their will is the point of holiness (nekudah shel kodesh) …

These fiery souls show their strength, that no fence or limit can restrain them, and the weak in the world that has been built, masters of manners and measures, are terrified by them …

These storms will yield bounteous rains; these dark clouds will be the preparation for great lights. “And from darkness and obscurity the eyes of the blind shall see.”

Immediately following his translation, Rabbi Naor provides several appendices and book reviews, some of which are germane to the understanding of The Souls of the World of Chaos, and some of which are not. This is Rabbi Naor’s style. He is a ma‘ayan ha-nove‘a, a gushing fountain. Once he wields his pen, it is difficult for him to arrest its motion. We are thus blessed with many excursions into realms of thought that educate and enrich us.

The following section, an important contribution of this volume, consists of Rabbi Naor’s copious notes on The Souls of the World of Chaos and the appendices. One of these notes touches lightly on Rav Kook’s thoughts on the ‘Erev Rav (the Mixed Multitude). In contradistinction to the Satmarer Rebbe who rendered such elements unredeemable, Rav Kook saw them as powerful souls destined to rejuvenate the spirituality of the world once they have undergone tikkun (fixing).

Rabbi Naor also serves as a conduit for Rav Kook’s son, Rav Zvi Yehudah’s elaborations and elucidations of his father’s perspectives, such as his attitudes toward secular studies and pursuits.

In sum, this work is an essential and worthy contribution to understanding the ideas by which Rav Kook, doubtless unintentionally, irked many of his peers. These same ideas are clearly the underpinnings of Rav Kook’s boundless ahavat Yisrael (love of the Jewish People), and his vast and profound love of humanity and creation. Sadly, one is hard-pressed to find similar attitudes on our contemporary scene. Perhaps this work will help some of us to reconnect to the master’s true perspectives.