There’s a story that mathematician and physicist John von Neumann was told that besides him, there were only five people in the world that truly understood quantum mechanics. He replied incredulously, “Really, who are they?”

I don’t know how many people truly understand the esoteric works of Rav Avraham Kook, but I know Rabbi Bezalel Naor is one of them. As a master of kabbalah, many of Rav Kook’s writings are nearly impenetrable. Yet Naor is able to extract some of those secrets and bring them to the light of the uninitiated in mysticism and the writings of Rav Kook.

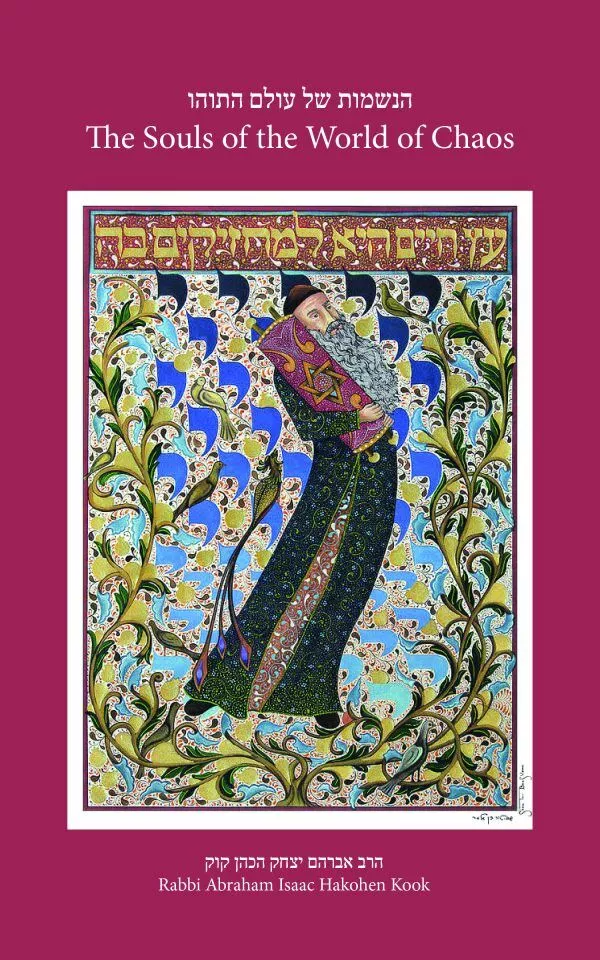

One of those mysterious writings is “HaNeshamot shel Olam HaTohu,” literally “The Souls of the World of Chaos.” The volume was first published in 1913 by Kodesh Press. It was written to deal with and support the new immigrants of the second aliyah of Jews to Israel between 1904-1914. Many of these immigrants were from Eastern Europe and lacked any formal Jewish education. Rav Kook saw these Jews as virtuous people, involved in rebuilding Israel.

While not his intent, Naor’s elucidation of Rav Kook’s views here shows why those in the Old Yishuv went apoplectic over Rav Kook’s love for these Jews. Rav Kook saw these non-religious Jews as part of God’s divine plan for rebuilding the Holy Land. The Old Yishuv saw them as unrepentant rebels and sinners who deserved to be vomited out of Israel.

Comprising but a few hundred words, what it lacks in length, “The Souls of the World of Chaos” makes up in depth. And Naor brings those impenetrable ideas to light. Rav Kook’s language is allusive and aphoristic. And making sense of those terse aphorisms, which use kabbalistic imagery and language, is what makes Rav Kook so challenging.

Kook saw in these non-religious pioneers the chaotic lights that would, in the future, be the bright lights in a redeemed Israel. The Gemara in Sotah says that one should push away with their left hand and draw a person closer with their right. Rav Kook was the type that would attempt to draw everyone near with both hands. And that is why he was so beloved by those who pushed their own religious observance away with both hands.

The essay is based on the kabbalistic approach of the Ari, which is another encyclopedic task to understand. And it takes Naor a few chapters to lay out the groundwork to explain that.

In his journey to mastering the Torah of Rav Kook, Naor was also a close student of his son Rav Tzvi Yehudah Kook. Rav Kook’s boundless love for all Jews was legendary. When Naor mentioned this to Tzvi Yehudah, his response was an outburst of hearty laughter. Containing himself, he explained that his father didn’t only love the Jewish people — he loved the entire world, even the vegetable and mineral kingdoms.

Naor also throws in a few stunners. The biggest of which is that Rav Zadok HaKohen of Lublin didn’t mention Rav Moshe Chaim Luzzatto (Ramchal) in any of his works, as he suspected Ramchal of being a Sabbatian. And by the same token, Rav Haim Yosef David Azulai (Chida) omitted Ramchal in his “Shem HaGedolim” for the same reason.

Additionally, the book also includes two of Naor’s book reviews, that of “Toward the Mystical Experience of Modernity: The Making of Rav Kook, 1865-1904” by Dr. Yehudah Mirsky and Dr. Hagay Shtamler’s “Eight Letters from Rabbi Zvi Yehuda Kook.”

Rav Kook was a cosmic thinker and a poetic soul. No one would be so naïve as to think they could understand Rav Kook’s personality. And yet, his personality was his writings. He was obscure and elusive, yet Naor masterfully removes a few of those husks, and opens the very bright, almost blinding light of the genius of Rav Kook.

This review by Ben Rothke originally appeared in Jewish Link.