Parashat Bo

The Enigmatic Existence of Evil

Bo el Par’oh / Come to Pharaoh

Bezalel NaorThe Torah portion begins with the words “Vayyomer YHWH el Moshe, Bo el Par’oh” (“The Lord said to Moses, ‘Come to Pharaoh’”).[1] Moses is commanded by God to appear before Pharaoh and demand that Pharaoh send free the People of Israel. The obvious question arises. Would it not be more correct syntactically to command “Lekh el Par’oh” (“Go to Pharaoh”), rather than “Bo el Par’oh” (“Come to Pharaoh”)?

The Rebbe of Kotsk, Rabbi Menahem Mendel Morgenstern (1787-1859), one of our boldest and most daring thinkers, replied that one must not forget who is speaking: God. So the statement is formulated from God’s perspective. From God’s perspective, it is perfectly correct to say “Come to Pharaoh” because God is found right there in the very midst of Pharaoh!

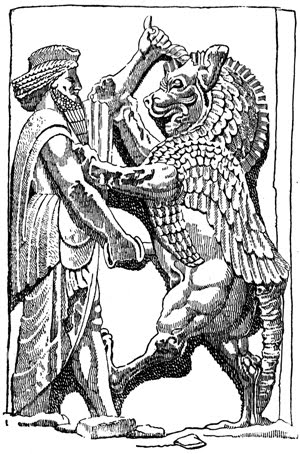

This is an extremely powerful, even brutal realization that goes to the very heart of the problem of evil. All philosophic systems must ultimately come to terms with the problem of evil. If God is good, then how does evil arise in this universe? The Persian religion of Zoroastrianism was conveniently able to posit two opposite forces at work in the world: Ahura Mazda (or Hormazd, Hormoz),[2] the god of good and light, versus Ahriman, the god of evil and darkness. However, the ancient Israelite prophet Isaiah railed against this dualistic perception of reality, upholding a strict monotheism, a single deity who “yotser ‘or u-bore hoshekh, ‘oseh shalom u-bore ra’, ani YHWH ‘oseh kol eleh” (“forms light and creates darkness, makes peace and creates evil; I am the Lord Who does all this”).[3]

With this sharp, epigrammatic koan of the Kotsker Rebbe, there is driven home to us in the most forceful manner that Pharaoh, the very symbol of evil, has no existence independent of God. Ultimately, the evil in the world is authored by God. Judaism could not afford the dualism of the Persian prophet Zoroaster (or Zarathustra). In the simple, yet eloquent words of the Prophet Isaiah: “bore ra’” (“[The Lord] creates evil”).

In our daily morning prayer established by the Sages who postdated Isaiah, Isaiah’s stark, shocking statement has been emended to read: “Barukh ata YHWH, Eloheinu, melekh ha-‘olam, yotser ‘or u-bore hoshekh, ‘oseh shalom u-bore et ha-kol” (“Blessed are you, Lord, our God, King of the Universe, who forms light and creates darkness, makes peace and creates the all”).

Rav Kook explains the difference between the Prophet Isaiah’s formula and that instituted by the Sages in our prayer. Isaiah was describing the “facts on the ground,” so to speak. One cannot deny the facticity of evil in our world. Unfortunately, the world abounds in evil.

The Prophet described the reality of our plane of existence. The Sages understood that on a higher level of reality (referred to as “the All”), the seemingly discrete, disparate, disjoint elements bond together in a simple unicity:

The prophecy, which is intended to inculcate a moral lesson in opposition to philosophies that would undermine monotheism, is stated in terms of human perception: “creates darkness,” “creates evil”… But we in our prayer, inasmuch as it our objective to tell the truth of the honor of the Lord, are correct in saying “creates the all.”… But in order “to mention the attribute of day by night, and the attribute of night by day,”[4] i.e., the principle of the singularity of divine rule throughout all the opposite manners in which existence is governed—both general and specific—we mention too that which is our common perception: “creates darkness.”

However, since the purpose of the blessing is also to bless the Lord for His lovingkindness—“‘olam hesed yibaneh” (“the world is established with lovingkindness”)[5]—it is worthy to conclude the blessing with the acknowledgment of the truth, that the Lord created no evil, and there is in existence no absolute evil, and the perceived evil is joined to the totality to perfect the good, so that evil is subsumed under the term “the All.”[6]

According to Rav Kook, the relation of the text of the prayer to that of the prophecy is exactly the reverse of what we have generally been led to believe. Most of us assume that Isaiah spoke truth itself and that the Rabbis in formulating the prayer “toned down,” ameliorated or even censored that truth, substituting a euphemism “all” for Isaiah’s unflinching “evil.” Comes Rav Kook and tells us the exact opposite. The ultimate truth is that formulated by the Sages, the Men of the Great Assembly: In reality there is no evil. Once evil has been grasped as part of the totality of existence, it disappears from our vision. It was the Prophet Isaiah, who for the purposes of moral exhortation in combatting philosophies that would deny pure monotheism, overstated the case for evil, couching reality in terms convenient to the common perception of man.

Although Rav Kook chalks the difference of the prophecy and the prayer to their varying objectives—moral exhortation versus singing the praises of God, Who is ultimately a loving God—one is tempted to explain the difference in terms of the prophet’s and sage’s differing perceptions of reality. When confronted with the problem of evil, the purview of the Prophet is circumscribed; the Sages’ grasp of reality is more comprehensive. At this point, one might invoke the famous maxim: “Hakham ’adif mi-navi.” (“The sage is superior to the prophet.”)[7] Based on their theodicy, the Men of the Great Assembly actually surpassed the Prophets.[8]

[1] Exodus 10:1.

[2] See TB, Gittin 11a and Tosafot ad locum, s.v. Hormin; TB, Sanhedrin 39a and Tosafot ad loc., s.v. Hormiz.

[3] Isaiah 45:7. The passage occurs within the context of a prophecy to Cyrus, King of Persia.

[4] TB, Berakhot 11b.

[5] Psalms 89:3. See also Genesis Rabbah 8:5: “Lovingkindness says, ‘He [i.e., Adam] should be created.’” It should be noted however that the words “asher amar ‘olam yibaneh” (“which said the world should be created”) are lacking in the original of ‘Eyn Ayah, and would therefore appear to be a gloss of Rabbi Tsevi Yehudah Hakohen Kook to his father’s work. (See next note.) The present writer hopes one day to deal with this and other issues concerning the composition of Rav Kook’s commentary to the Prayer Book.

[6] Rabbi Abraham Isaac Hakohen Kook, Siddur ‘Olat Re’iyah, Vol. I, p. 239; idem, ‘Eyn Ayah (Filber ed.), Berakhot, Chap. I, par. 160. The text of ‘Olat Re’iyah differs from that of ‘Eyn Ayah (Rav Kook’s commentary to ‘Eyn Ya’akov). Rav Kook’s son, Rabbi Tsevi Yehudah Hakohen Kook (1892-1981) adapted the section from ‘Eyn Ayah to the Siddur.

[7] TB, Bava Batra 12b.

[8] See Yer. Berakhot 7:3; TB, Yoma 69b; Rabbi Isaac Hutner, Pahad Yitshak—Hannukah, Ma’amar 8.

Rabbi Isaac Hutner was a disciple of Rav Kook during Rabbi Hutner’s early years in Jerusalem. (However, Rabbi Ahron Soloveichik once communicated to this writer in private conversation that he felt it an inexactitude to use the term “talmid” [disciple] to describe Rabbi Hutner’s relation to Rav Kook. Rabbi Hutner was the private teacher of Rabbi Ahron Soloveichik during the latter’s youth in Warsaw.)