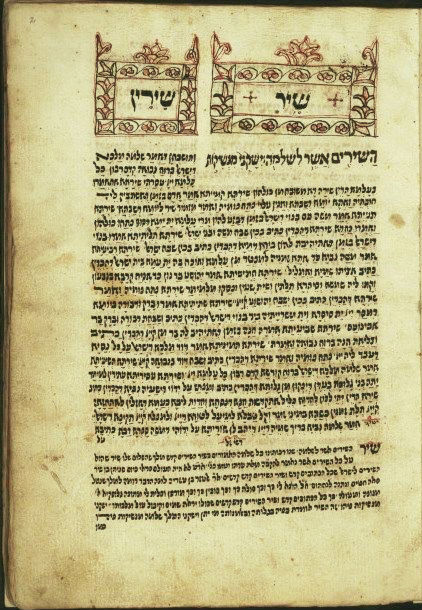

The Orality of Shir ha-Shirim and of Tikkunei Zohar

by Bezalel Naor

Without doubt, the most widely known passage of Tikkunei Zohar, an early fourteenth-century composition, is the Introduction, “Patah Eliyahu” (“Elijah opened”). Its popularity is attested to by the fact that it is printed in numerous siddurim (prayer books) of the Sephardic and Hasidic communities, upon whose liturgy Kabbalah has had the most impact.[1]

The Introduction provides an embodiment of the Ten Sefirot or divine attributes, working its way down the divine frame, as it were, coordinating various limbs of the body with their corresponding sefirot:

Hesed [Kindness] is the right arm;

Gevurah [Power] is the left arm;

Tif’eret [Splendor] is the torso;

Netsah [Eternity] and Hod [Glory] are the two thighs;

Yesod [Foundation] is the end of the torso, the symbol of the sacred covenant;[2]

Malkhut [Kingship] is the mouth, which we refer to as the Oral Torah.

Hokhmah [Wisdom] is the brain…

Binah [Understanding] is the heart…

Keter ‘Elyon [Supreme Crown] is the crown of kingship.[3]

What is otherwise an orderly downward articulation of the limbs, abruptly shifts direction at Malkhut, whereupon we jump back up to the mouth. Many a reader has been perplexed by this anomaly.[4]

*

It is widely held by scholars that the Jewish mystical literature that comes under the rubric of Shi‘ur Komah (Body of God) has its origins in Shir ha-Shirim, Song of Songs.[5]

, school job-time is not enough. To make sure your “big stones” are in the vase, plan the use-of-time of your entire week, Monday to Sunday, from wake up time to bedtime … This schedule must indicate your courses, but also personal work time, extracurricular activities, transportation, regular recreation … Use the tool that suits you: a large cardboard table that you put on the wall facing your desk, a classic paper diary, or a free calendar software to download on the internet that you can print or synchronize with your smartphone. The visuals will use different colors for personal work, lessons, sport, outings …

Song of Songs contains several catalogs in sequence of segments of the male or female body. These catalogs of body parts have come to be known in scholarly studies of the Song by the technical term wasf, an Arabic word meaning “description.” (Wasfs are common in modern Arabic poetry.)[6]

There are four wasfs in Song of Songs. Three describe the body of Shulamith (Song of Songs 4:1-5; 6:4-7; 7:1-6); one describes that of Shelomo (Song of Songs 5:10-16). The first three proceed from top down. The fourth works its way up from the feet of Shulamith. (As it begins by calling Shulamith to dance, the focus initially is upon her feet.)

If we pay close attention to the wasf of the dod, the male lover, we should notice a peculiarity:

“I adjure you, O daughters of Jerusalem, if you find my beloved, what will you tell him? That I am lovesick.”

“In what way is your beloved more than another beloved, O fairest among women? In what way is your beloved more than another beloved, that you have adjured us so?”

“My beloved is shining white and ruddy, prominent among ten thousand.

His head is purest gold; his locks are curls, black as the raven.

His eyes are like doves by the brooks of water; bathing in milk, dwelling by a pool.

His cheeks are as a bed of spice, towers of perfumes; his lips are lilies, dripping flowing myrrh.

His arms are rods of gold inset with beryl; his belly polished ivory overlaid with sapphires.

His thighs are pillars of marble, set upon sockets of gold; his look like Lebanon, choice as the cedars.

His mouth is sweet, and all of him is delight.

This is my beloved and this is my friend, O daughters of Jerusalem.”

(Song of Songs 5:8-16)

As one can readily see, the wasf proceeds in orderly fashion from the head, down through the arms, the belly and the thighs, to—the mouth? At “hiko” (literally, “his palate”) the flow chart has abruptly reversed direction.

Bible scholar Robert Alter provides an answer:

“The reversion to the mouth does not really violate the vertical movement of the poem downward because it is a kind of summary at the end: the beloved, having canvassed her lover’s beauty from head to foot, returns to the physical site of those kisses that epitomize physical intimacy with him and give her such gratification.”[7]

Be that as it may. Whatever the explanation for the reversal of direction, one thing is certain: Patah Eliyahu of Tikkunei Zohar has patterned itself after the wasf of Shir ha-Shirim, jumping from the lower portion of the male anatomy to the mouth. And from this mouth, proceeds the (Oral) Torah, in conformity to the Targum’s rendition of “hiko mamtakim” (“his mouth is sweet”):

Malei morigoi metikan ke-duvsha.

The words of His palate are sweet like honey.

[1] “Patah Eliyahu” is generally printed in the beginning of the siddur before the commencement of the Morning Prayer. An exception is the siddur of Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi (known in Lubavitch as the Siddur ‘im DA”H, or colloquially as “Alter Rebbe’s Siddur”) where it precedes the Afternoon Service on the Eve of the Sabbath.

[2] I.e. the phallus.

[3] Siddur Eitz Chaim: The Complete Artscroll Siddur (Nusach Sefard), transl. Rabbi Nosson Scherman (Brooklyn, NY: Mesorah Publications, 1985), pp. 11, 13.

In the Kabbalistic tradition, the “shalosh rishonot” (first three sefirot of Keter, Hokhmah and Binah) and the “sheva‘ tahtonot” (seven lower sefirot of Hesed, Gevurah, Tif’eret, Netsah, Hod, Yesod and Malkhut) are treated as two discrete units. In this study, our focus is strictly upon the “sheva‘ tahtonot.”

[4] Rabbi Isaac Hutner, Rosh Yeshivah of Metivta Rabbenu Chaim Berlin, was forced to conclude that Tikkunei Zohar employs peh (mouth) in this context as an oblique reference to the lower female anatomy. (Quoted in Rabbi Yisrael Eliyahu Weintraub, Nefesh Eliyahu: Hakdamot u-She‘arim [n.p., 2002], Letters, Letter 19 [p. 69].) See Proverbs 30:20: “So is the way of an adulterous woman: She ate, and wiped her mouth (u-mahatah fihah).” An extension of this euphemism would be the Mishnaic locution “ra’uha medaberet” (“they saw her speaking”) (m. Ketubot 1:8). See the Talmud’s explanation of Rav Asi’s opinion in b. Ketubot 13a. In y. Ketubot 1:8 there exists but the single opinion that “medaberet” refers to sexual intercourse and that Rabbi (i.e. Rabbi Judah the Prince), editor of the Mishnah, employed a euphemism (“lashon naki”). (One should also note that the Yerushalmi does not reference the verse in Proverbs. Though the commentaries Korban ha-‘Edah and P’nei Moshe, influenced by the Bavli, invoke that verse, there is no indication that the Yerushalmi is of a like mind.) See also b. Menahot 88a and Rashi ad loc., s.v. peh she-le-matah.

Though the solution offered is certainly ingenious, it is problematic, to say the least. Taken at face value, it would posit an androgynous body of God. That objection might be overcome by assuming that Tikkunei Zohar is imaging the body of Adam Kadmon before the mythic “nesirah” (splitting) and the emergence of woman as a separate body, a distinct entity apart from man.

See the earlier Sefer ha-Bahir (referred to by Nahmanides in his commentary to the Pentateuch as “Midrash Rabbi Nehunyah ben Hakanah”):

The Holy One, blessed be He, has seven holy forms, and they all have [something[ corresponding in man, for it says, “In the image of God He created him” [Genesis 1:27]. And these are: the right and left thigh; the right and left hand; the torso, and the berit (covenant). All told six.

But you said, “Seven”?

It is seven with his wife, as it is written, “And they shall become one flesh’ [Genesis 2:24].

But she was taken from his side (mi-tsal‘otav), as it is written, “He took one of his sides (mi-tsal‘otav)” [Genesis 2:21]. Does he have a tsela‘ (side)? Yes, as the Targum translates, “U-le-tsela‘ ha-mishkan” [Exodus 26:20]: “Ve-li-setar mashkena” (“And for the side of the Tabernacle”).

(Sefer ha-Bahir, Amsterdam 1651, facsimile edition in The Book Bahir, ed. Daniel Abrams [Los Angeles: Cherub Press, 1994], p. 281)

The description of the anatomy of the male (two thighs, two hands, torso and “covenant”) lines up with that of Tikkunei Zohar—with the exception of the “mouth.” This is also the reading of the Bahir preserved in the Hashmatot printed at the conclusion of Rabbi Reuben Margaliot’s edition of Zohar I, 264b (chap. 38) and in the “Hiddushei ha-Bahir” printed in the Cremona 1558 edition of Zohar I, 32a-b (facsimile in Daniel Abraham’s edition of Bahir, p. 246).

For variae lectiones (that will not tally with Tikkunei Zohar’s configuration), see Sefer ha-Bahir, Margaliot edition, par. 172 (p. 75, note 3); and Abrams edition, par. 116 (pp. 200-201, based on Munich manuscript with variants of Vatican ms.). See further Abrams ed., p. 42 (for variants of Moscow mss. and JTSA ms.).

Assuming that the Rosh Yeshivah is correct in translating “peh” in Tikkunei Zohar as the feminine orifice, we might say that whereas Sefer ha-Bahir imaged Adam Kadmon after the splitting of man and woman into two bodies, Tikkunei Zohar addressed the original androgynous configuration.

Putting that grievance aside, we would still be hard-pressed to account for the correlation of this orifice (the peh she-le-matah, as opposed to the peh she-le-ma‘alah) with the Oral Law (Torah she-be-‘al peh). That, it seems to me, is a more basic objection.

Par contre, Rabbi Weintraub (Nefesh Eliyahu, Letters, pp. 70-71) upheld the simple understanding that the mouth referred to in Tikkunei Zohar is in the head, not the lower extremity. He furthermore endorsed the explanation of Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi, Torah ’Or (Brooklyn: Kehot, 1972), Ki Tissa, 111c-d, based on the verse in Ecclesiastes 8:4: “devar melekh shilton” (“the king’s word [is] power”). See Nefesh Eliyahu, Letters, pp. 69, 71.

[5] Scholem writes:

The fragment in question [i.e. Shi‘ur Komah], of which several different texts are extant, describes the “body” of the Creator, in close analogy to the description of the body of the beloved one in the fifth chapter of the “Song of Solomon,” giving enormous figures for the length of each organ.

(Gershom G. Scholem, Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism [New York: Schocken Books, 1971], pp. 63-64)

See further Gershom Scholem, On the Mystical Shape of the Godhead (New York: Schocken Books, 1991), pp. 22-23, 30-33; idem, Origins of the Kabbalah (Princeton University Press, 1990), pp. 20-21; idem, Jewish Gnosticism, Merkabah Mysticism and Talmudic Tradition (New York, 1960), pp. 38-40; Saul Lieberman, Midreshei Teiman (Jerusalem, 1940), pp. 13-17; idem, Appendix D to Scholem, Jewish Gnosticism, Merkabah Mysticism and Talmudic Tradition, pp. 118-126; Arthur Green, “The Song of Songs in Early Jewish Mysticism,” in The Song of Songs: Modern Critical Interpretations, ed. Harold Bloom (New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 1988), pp. 143-145.

[6] See Marcia Falk, “The Wasf,” in The Song of Songs: Modern Critical Interpretations, 67ff.

[7] The Hebrew Bible, vol. 3: The Writings/Ketuvim, transl. with commentary, Robert Alter (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2019), p. 605, n. 16.

I very much enjoyed this article. I will note that the Da’at Mikrah commentary on Shir HaShirim gives the same explanation as you bring from Robert Alter and I believe is an earlier source (1973).

Besides the Jerusalem Talmud (which was the chief source) and the Pesi?ta de-Rab Kahana, the direct sources used by the redactor are Genesis Rabbah and Leviticus Rabbah. The material borrowed from these sources constitutes a large part of the midrash, and it throws a light also on the redactor’s method. The remainder of the midrash must have originated in midrashic collections which are no longer extant, and from which the redactor borrowed all the comments that are found also in the Seder Olam, the Sifra, the Sifre, and the Mekilta, since it is not probable that he borrowed from these earlier midrashim. The midrash is older than Pesi?ta Rabbati, since the latter borrowed passages directly from it. As the Pesi?ta Rabbati was composed about 845 C.E., Shir ha-Shirim Rabbah must have been composed about the end of the h century. The midrash has been edited and commented together with the other Midrash Rabbot, and has been edited separately and supplied with a commentary, entitled