BOOK REVIEW BY BEZALEL NAOR

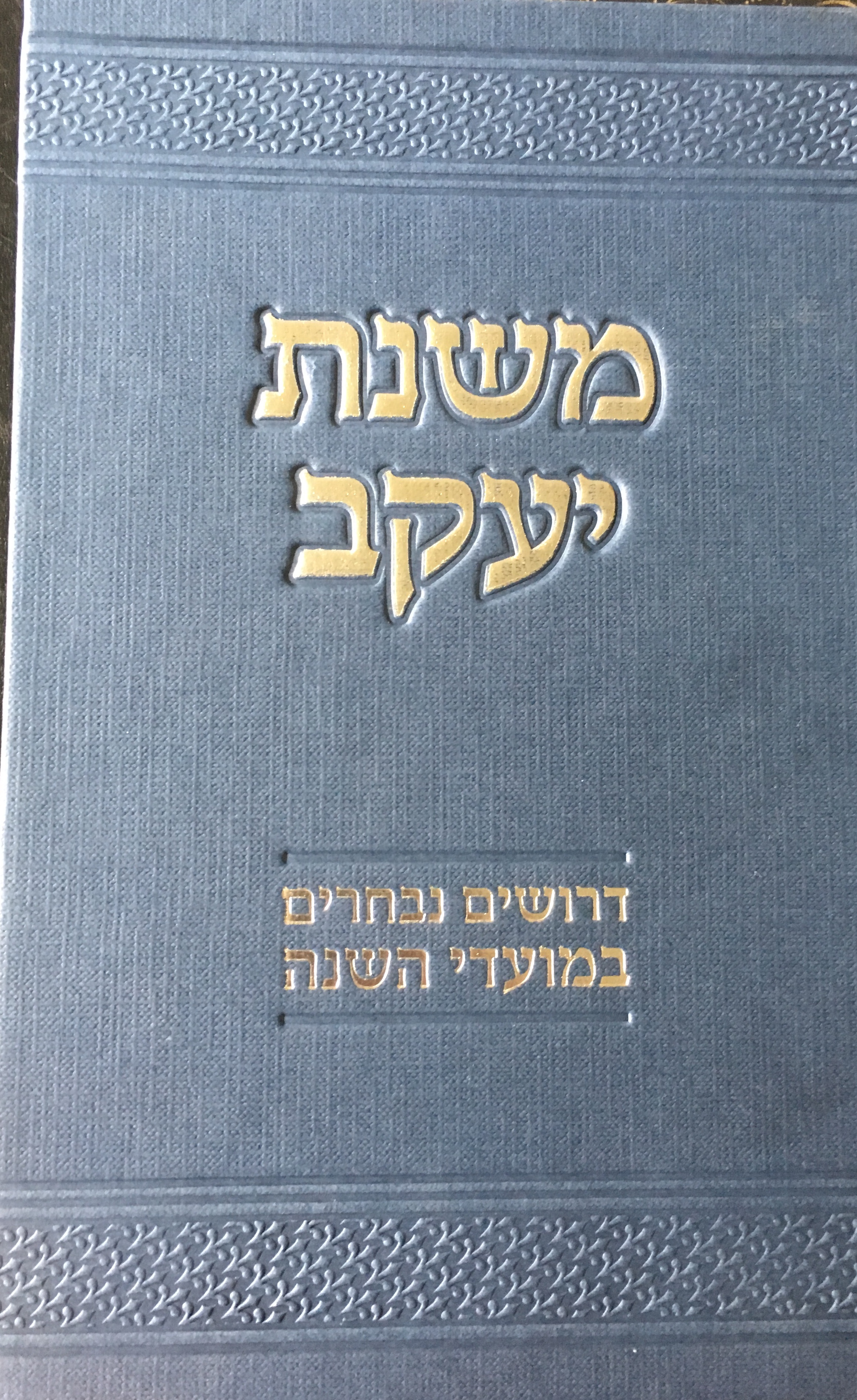

Shnayor Z. Burton, Mishnat Ya‘akov: Derushim Nivharim be-Mo‘adei ha-Shanah (5779/2019)

Rabbi Shnayor Burton is a distinguished Talmudic scholar who resides in the Flatbush section of Brooklyn. This is his second work of Jewish Thought.

In 2017 he published Orot Ya‘akov: Derushim Nivharim be-Ma‘asei Avot. That volume focuses on the lives of the patriarchs of our nation, Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, whose sagas are recorded in the Book of Genesis.

The present sequel volume contains derushim (homilies) on the cycle of the year, the Sabbath and festivals.

In the introduction to the work, the author calls our attention to the first derush, “Torat Moshe ve-Derekh ha-Nevi’im” (“The Torah of Moses and the Way of the Prophets”). It is to this seminal thought that I shall devote my remarks.

The three outstanding Jewish theologians of twentieth-century America—Abraham Joshua Heschel, Isaac Hutner and Joseph Baer Soloveitchik (in alphabetical order of their last names)—in one context or another, all dwelled on the phenomenon of the prophets of Israel.

In the case of Rabbi Soloveitchik, it was the spartan yet incisive observation that the entire project of the prophets consists of a divulgence of the divine attributes, to the end of imatatio dei. Rabbi Soloveitchik’s remarks are predicated on Maimonides, Hil. De‘ot 1:6: “Thus too, the prophets described God by all the various attributes, ‘long-suffering’ and ‘abounding in kindness,’ ‘righteous’ and ‘upright,’ ‘perfect,’ ‘mighty’ and ‘powerful,’ and so forth, to teach us that these qualities are good and right, and that a human being should cultivate them, and imitate [God], as much as one can.”[1]

Rabbi Hutner’s perception of the prophets took the form of an intriguing exploration of their silence when confronted with the problem of theodicy. For the Pahad Yitzhak (as for Rashi earlier), the essence of the prophet is speech (navi from niv) and the ability to describe the divine attributes. With the destruction of the Temple there occurred a cosmic breakdown and a muting of the prophetic voice.[2]

Finally, as a young man, Abraham Joshua Heschel wrote his doctoral dissertation on the subject. The Prophets is a massive work that attempts to arrive at the essence of Israelite prophecy. Painstakingly, we are introduced to a God who is—to employ Heschel’s term—“anthropopathic.” God commiserates with man and shares in man’s suffering. This is a reversal of Maimonides’ teaching. The divine attributes are not virtual realities designed for human imitation. They are reality!

*

Our author, whether consciously or not, continues the conversation. He sets up the opposition of the Torah of Moses and the Way of the Prophets. Some of the ideas are already familiar to us, but there is something fresh, something new here, specifically the value assigned to the korbanot, the sacrifices in the Temple. For Rabbi Shnayor Burton, the sacrificial cult is not just one aspect of the Torah, but its essence. And it is the sacrifices which are the escarpment between the two surfaces of the Torah and the Prophets.

The prophets—Isaiah, Jeremiah—rail time and time again against the sacrificial cult. Why? Simply, theirs is a critique not so much of the institution itself, but of the corruption and the moral turpitude that came to be associated with it.

In Rabbi Burton’s presentation we wake up to the realization that the way of the priests and the way of the prophets are in a sense antithetical to one another. If the prophets bestowed upon us knowledge of God’s ways, the sacrifice takes us beyond that to the unfamiliar and ultimately unknowable. The act of bringing a sacrifice is an act of surrender, an admission of ignorance. The way of the prophets is the way of knowing. The way of the sacrifices is the way of not-knowing.

The prophets allow us to know God’s goodness.[3] The Torah takes us beyond human ken, beyond earthbound notions of “God,”[4] beyond “good.”[5] Torah is the Absolute, the Prophets are the attributes.

*

Perhaps this is the secret of Maimonides’ downgrading of the sacrifices in his philosophic work, the Guide. Whereas in his halakhic work, Mishneh Torah, the sacrifices enjoy a robust life (something unseen in the several centuries intervening between the completion of the Talmud and Maimonides’ own day), in the Guide the sacrifices suffer immensely, as they are held up to the scrutiny of comparative religion and reduced to the primitive state of Near Eastern civilization. Many over the centuries, including Maimonides’ greatest admirers, have been perplexed how the same author could so abruptly shift gears.

I would suggest that in Mishneh Torah Maimonides writes from the perspective of Moses the legislator. In the Guide, which according to scholarly consensus is Maimonides’ promised Book of Prophecy,[6] he writes from the perspective of the prophetic—not the Mosaic—tradition. And that tradition, which constitutes the way of knowing God, carries with it, eo ipso, an adversarial attitude to the very institution of sacrifice.

*

Unbeknown to our author, some of the themes that he addresses were encapsulated by Rav Kook in an enigmatic code.

The verse in Exodus 22:1 reads: “If the thief is discovered while tunneling in…” The Hebrew word for the underground (or tunnel) is “mahteret.” Rav Kook envisioned this as two words: mah torat. Mah is the number forty-eight, symbolizing the forty-eight prophets.[7] Torat is Torah in the nismakh (construct) form. The thief is an allusion to Jesus, who was depicted in the old work Toledot Yeshu as a “gonev shem shamayim,” someone who absconds with the divine name.

What appeared to Rav Kook in a kabbalistic reverie was that the “theft,” the misappropriation perpetrated by Christianity, consisted in the prioritization of the Prophets over the Torah. In mainstream Judaism, the Torah is primary and the Prophets secondary. Christianity reversed the order making the Torah secondary (“nismakh”) to the Prophets. Christianity latched onto the compassion of the prophets while obsoleting the laws of the Torah.[8]

(As a student of students of Rav Kook, I might add a postscript that in Catholicism, the singular divine “I” of Anokhi, the undefinable, indescribable Giver of the Torah, was fractured into a trinity of attributes.)

*

The saintly “Hafets Hayyim,” as he was known, Rabbi Israel Meir Kagan, pushed young Talmudists, especially kohanim such as himself, to become conversant with the fifth order of the Talmud, Kodashim, which deals with sacrifices. To this end, he himself authored the digest Likkutei Halakhot, accomplishing for the exotic order of Kodashim what Rabbi Isaac Alfasi in his Halakhot had accomplished for the other actual orders of the Talmud.

The Hafets Hayyim explained that the rebuilding of the Temple is imminent and therefore, the teachers of Torah must be competent to rule in matters pertaining to the Temple service.

That the sacrifices have seized the imagination of a young, talented thinker with such force, may be indicative of our proximity to the Temple. The Beit ha-Mikdash will require not only poskei halakhot (decisors) to adjudicate thorny matters of ritual law, but also hogei de‘ot (thinkers) to breathe life into an otherwise moribund service, and to make peace between the way of knowing and the way of not-knowing.[9]

______________

[1] See Rabbi J.D. Halevi Soloveitchik, Shi‘urim le-Zekher Abba Mari, vol. 2 (Jerusalem: Mossad Harav Kook, 2002), “Mehikat Hashem” (pp. 188-189).

[2] See Rabbi Isaac Hutner, Pahad Yitzhak: Kuntres ve-Zot Hanukkah (New York, NY, 1989), ma’amar 8 (pp. 63-75); Rashi, Exodus 7:1.

Textual problems arise in regard to this ma’amar. The key phrase “ro’eh ve-shotek” (“He sees and is silent”) does not occur in the Bavli version of the crisis (Yoma 69b), rather in the Yerushalmi version (Berakhot 7:3, Megillah 3:7). And in the Yerushalmi, God’s silence does not result in the muting of prophecy. On the contrary, “It is fitting to call this [God] ‘gibbor’ (‘mighty’), for He sees the destruction of His house and is silent!” By fusing Bavli and Yerushalmi, Rav Hutner has in effect created his own narrative.

[3] One ventures that this is the significance of the term “nevi’im tovim” (“good prophets”) in the blessing preceding the haftarah, the reading from the Prophets. The raison d’être, the entire project of the prophets, is to manifest the goodness of God.

[4] See Exodus 6:3.

[5] See Maimonides, Guide of the Perplexed I, 2.

[6] See Shemonah Perakim (Maimonides’ introduction to Avot), chap. 7 (Kapah ed., p. 260, col. a); and the introduction to the Commentary to the Mishnah, Kapah ed., p. 5, col. a.

[7] b. Megillah 14a.

[8] See Rabbi Abraham Isaac Hakohen Kook, Kevatsim mi-Ketav Yad Kodsho, vol. 1, ed. Boaz Ofen (Jerusalem, 2006), Pinkas Rishon le-Yaffo, para. 43 (pp. 98-99); Rabbi Hayyim Avihu Shvarts, Mi-Tokh ha-Torah ha-Go’elet, vol. 3 (Jerusalem, 1989), p. 225; Rabbi Tsevi Yehudah Hakohen Kook, Li-Netivot Yisrael, vol. 2 (Jerusalem, 1979), “Ha-Pesha‘ be-Yisrael” (pp. 60-61).

[9] See Rabbi Nahman of Breslov, Likkutei Moharan I, 6:4, 7; II, 7:7.